Introduction to Manipulation Notes

Grasp Analysis

Grasping is a fundamental skill in manipulation and has broad application to many tasks. While the term “grasping” has many interpretations and definitions, here we will refer to an object rigidly held by the robot as a grasp. Specifically, the robot is permitted to make contact with the object at a known number of points and is only able to impart forces through these contacts. If the set of forces imparted to the object satisfy a set of requirements that we will study in this section, then the robot has successfully grasped the object. The goal of this section is to study the conditions under which a given grasp is stable. This is referred to as Grasp Analysis. In later chapters, we will dedicate time to Grasp Synthesis, where the goal is to compute a grasp rather than assume that one is given.

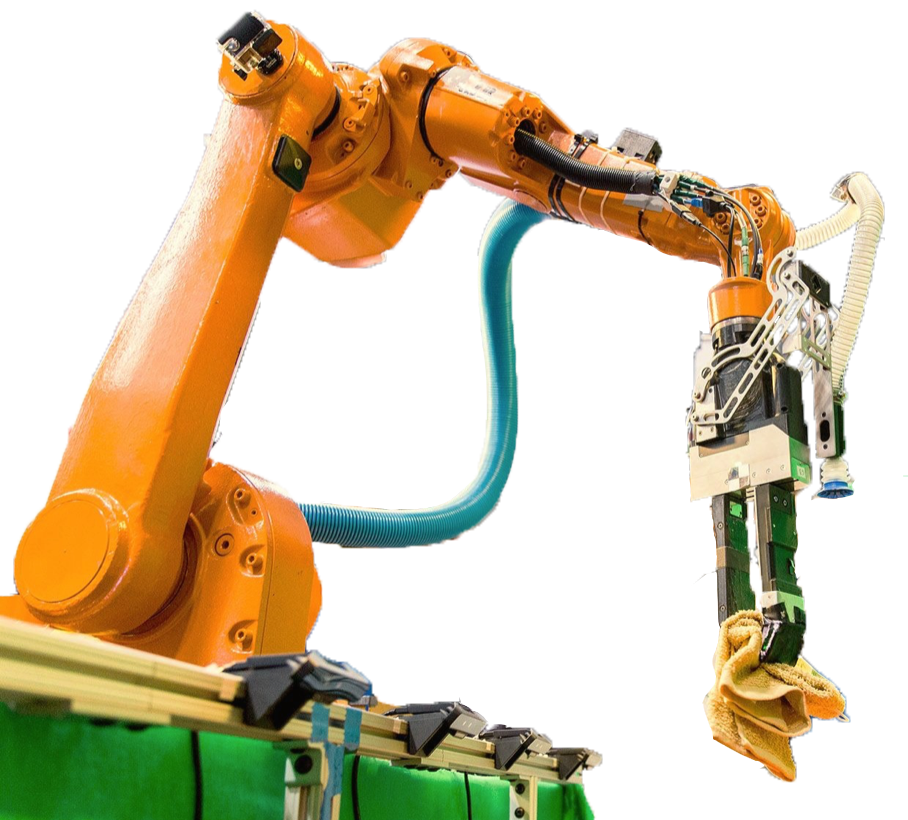

The robot can pick and place grasped objects and/or use them as tools to interact with its environment. A real-world example of a robotic system grasping objects autonomously is shown in Fig. 1.

In this section, we make the following assumptions:

- All bodies are rigid: This significantly simplifies the object and robot representations allowing us to use finite (and relatively small) configuration spaces. We also get well-defined and relatively simple mappings between contact forces and object wrenches as well as simplified frictional interactions. Note that the object will never deform, no matter how hard we grasp it.

- Static: We will only consider objects that are static. This means we are given a snapshot of a grasp and our goal is to evaluate it. We are not worried about how the grasp was achieved, only what would happen given the current configuration – i.e., is the current grasp stable.

- Coulomb Friction: A very reasonable approximation to the frictional interaction between the robot and object.

- Known Geometry: We’re going to assume that we a have access to precise object and robot poses as well as known object and robot geometry.

- Infinite Squeeze Force: We’re going to assume that the robot can apply as much torques as necessary with its joints. This assumption is more of a technicality because it is conceivable that the external force attempting to break the grasp is also infinite. In practice, all forces are finite and our analysis will hold assuming the actuators are strong enough.

In the remainder of this section we will develop the grasp matrix, a fundamental tool in analyzing grasp quality, and draw connections to the contact Jacobian we have studied previously. We will then use the grasp matrix to evaluate form and force closures of grasps to evaluate the stability of grasps. These properties are central to the task of planning for and controlling grasps and we will touch on these in subsequent chapters.

In the remainder, our analysis follows the excellent Grasping chapter of \citet{prattichizzo2016grasping} and we refer the reader to this text for further details.

Grasp Matrix

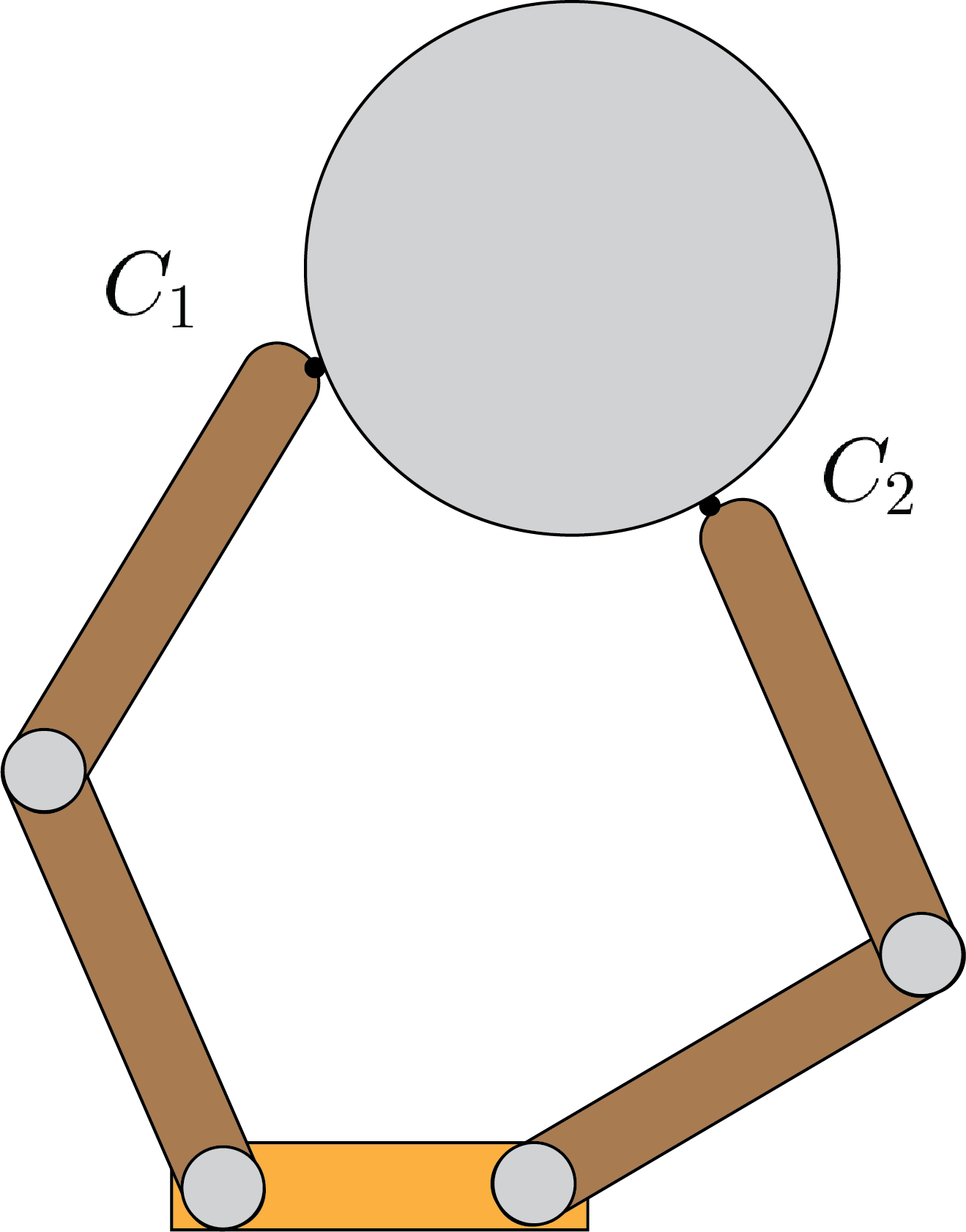

Let’s consider an object being grasped by our robot, e.g. the one depicted in Fig. 2. The robot makes $N$ points of contacts with the object. The forces imparted by the robot to the object are governed by Coulomb friction. We will restrict our selves to the class of point contacts. For this class, each contact force $\mathbf{f}_{c,i}$ for $i=1, …, N$ can be written in the contact frame as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{f}_{c,i} = \begin{bmatrix} f_n \\ f_{t,1} \\ f_{t,2} \end{bmatrix}\; \text{in 3D;} \quad \quad \mathbf{f}_{c,i} = \begin{bmatrix} f_n \\ f_{t} \end{bmatrix}\; \text{in 2D} \end{align*}\]

From Preliminaries section, we know that we can project this force into the reference frame of the object using the contact Jacobian:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{w}_i = \mathrm{J}_{c,i} \mathbf{f}_i \end{align*}\]where $\mathbf{w}_i$ denotes the wrench in the object frame corresponding to the force $\mathbf{f}_i$. Since $\mathbf{f}_i$ is governed by Coulomb friction, the corresponding wrench is due to the projection of the friction cone into the reference frame of the object. By summing up the individual contributions of all external forces applied by the robot to the object we have a composite friction cone, similar to the 2 point contact case in planar pushing. We may write:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{w} = \sum_{i=1}^N \mathbf{w}_i = \sum_{i=1}^N \mathrm{J}_{c,i} \mathbf{f}_i = \begin{bmatrix} \mathrm{J}_{c,1} & ... & \mathrm{J}_{c,N} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{f}_1 \\ ... \\ \mathbf{f}_N \end{bmatrix} = \mathrm{G} \mathbf{f} \end{align*}\]where $\mathrm{G}$ denotes the grasp matrix. In general, the grasp matrix is $6\times 3N$ dimensional for frictional point contacts with rigid bodies. Given the grasp matrix (which implicitly encodes the location of the grasps) and the coefficient of friction (to determine the friction cones), a grasp is fully identified. Note that the composite friction wrench has an identical definition to the grasp matrix.

In our derivation so far, we have implicitly assumed that the fingers of the robot are able to impart $\mathbf{f}_i$. In practice, the robots actuated joints can apply torques that are transmitted to the contact point through a set of contact Jacobians as well. We may write this as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{f}_i = \bar{\mathrm{J}}_{c,i} \mathbf{\tau} \end{align*}\]where we have used the bar notation to differentiate between the finger Jacobian and object Jacobian, and the robot actuation is denoted as $\mathbf{\tau}$. With this consideration, a grasp is fully defined by the grasp matrix $\mathrm{G}$, the robot Jacobians $\bar{\mathrm{J}}_{c,i}$, and the coefficients of friction at the points of contact.

One intuitive interpretation of the grasp matrix is that given a set of contact points and coefficients of friction, we can compute all the external wrenches we can apply to the object that can be resisted by the fingers. Another intuitive interpretation is that the grasp matrix qualifies the set of motions the object is not able to make given a grasp. In the following sections, we formalize these notions into a rigorous mathematical framework for grasp analysis.

Grasp Analysis - Form Closure

With the grasp matrix in hand, we are now staged to begin our discussion on useful types of grasps. We will begin with the notion of form closure. Intuitively, if the grasped object is in form closure then it is fully geometrically immobilized by the set contacts. We cannot perturb the object’s configuration without violating any contact constraints; i.e. non-penetration. This simply means that any change in the configuration of the object with respect to the robot would lead to penetration of the object and is therefore impossible. This intuitive explanation is precisely how we write down and solve for form closure.

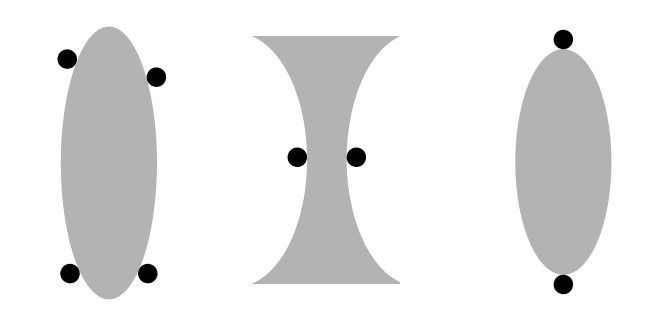

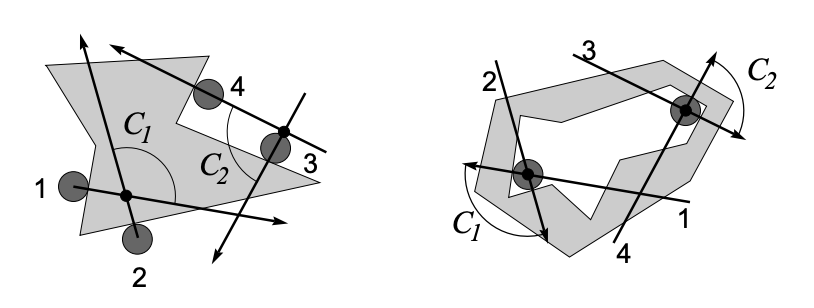

Before diving into the mathematical derivation, let’s go through some examples. Take a look at Fig. 3. Which of these grasps are form closures? The first grasp is in form closure of first order. The second grasp is not in form closure of the first order, but it is in form closure of the second order. The third grasp is not in form closure at all. To understand the form closure of the second grasp, try to imagine a change in configuration of the object that does not violate the non-penetration constraint. Can you find such a change?

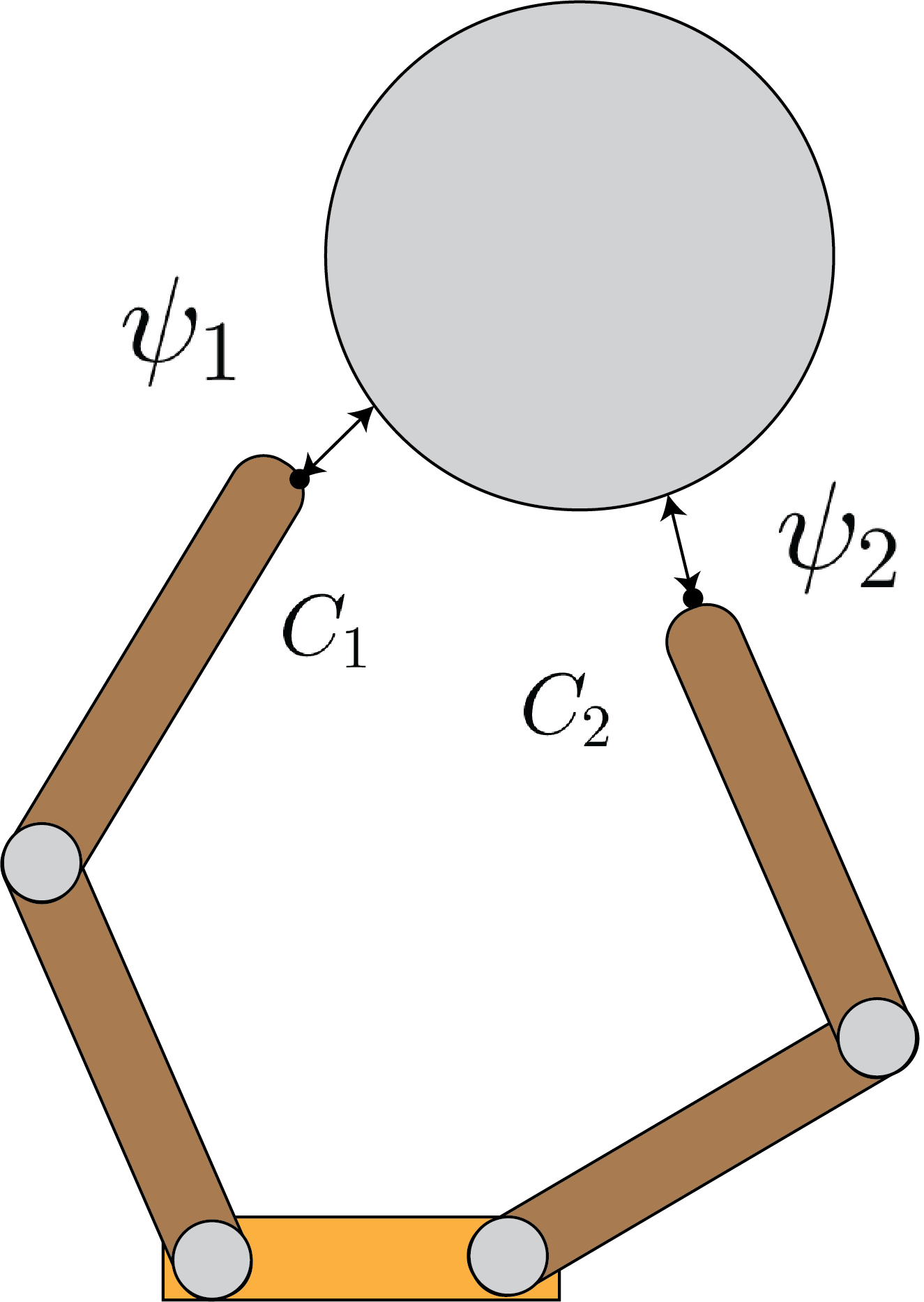

Now for th derivation: As in the previous subsection, let’s assume that there are a total of $N$ frictional contacts, each applying a force $\mathbf{f}_i$ at contact points $i=1, …, N$. For each contact point, we define a distance function $\psi_i(\mathbf{q}, \mathbf{q}_c)$ for $i=1, …, N$, where $\mathbf{q}$ denotes the object configuration and $\mathbf{q}_c$ denotes the configuration of the fingers. Together, these configurations specify the distance to contact for each contact point $i$. $\psi_i > 0$ implies separation, $\psi_i < 0$ implies penetration, and $\psi_i = 0$ implies contact. Let’s assume all $N$ contacts are active; i.e. that $\psi_i=0$ for all $i$. Fig. 3 illustrates the distance functions for the grasp depicted in Fig. 2.

For form closure to hold, we require that:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{\psi}(\mathbf{q} + d\mathbf{q}, \mathbf{q}_c) \geq = 0 \implies d\mathbf{q} = 0 \end{align*}\]where the expression is to be evaluated element-wise. Intuitively, if any infinitesimal perturbation to the configuration of the object results in separation without penetration, then form-closure is violated. Conversely, we cannot find any infinitesimal perturbation to the configuration of the object that does not violate the non-penetration constraint. While this constraint provides an effective definition for form closure, we cannot use it in its current form. The reason why we cannot use the constraints as they are is that it would require us to check them for all possible $d\mathbf{q}$. Since this change in configuration vector lives in $\mathbb{SO}(2)$ or $\mathbb{SO}(3)$, there is no way to do this. You’d have to sample every single change in configuration vector, and there are infinitely many of them.

You may be tempted to discretize and check at the discretization points, hoping that if the check holds at these points, then it should hold for points in between. This check not only has that big assumption we’d be worried about making, it would also be very expensive due to both the number of times we’d have to perform it (once per discretization point which is high-dimensional) and that it involves a collision check that can itself be very expensive (more on collision checking later in the notes).

An alternative approach is to think about the local change in contact point positions for an infinitesimal change in the object configuration. More specifically, we can look at the gradient of the distance functions as a function of the change in object configuration. This is a local approximation, specifically a first order approximation that we can write in the form of:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial \mathbf{\psi}}{\partial \mathbf{q}} d\mathbf{q} \geq 0 \implies d\mathbf{q} = 0 \end{align*}\]This first order approaximation of the form closure should look like the first term in the Taylor expansion approximation of the form closure expression. The interpretation is the same as before; however, to a first order approximation of perturbation. By itself, this approximation has not really fixed anything, we are still left with the original problem. However, the key insight is that we can relate the approximation to the grasp matrix.

To see how, first we note that since $\mathbf{\psi}$ is the distance function, it’s gradient is along the normal vectors of the contact frames at each contact point. We know that the grasp matrix is composed of the set of normal and tangential components of contact frames. Let’s denote the grasp matrix composed of only the normal contact vectors as $\mathrm{G}_n$. The condition above can equivalently be written as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G}^T_n \mathbf{v} \geq 0 \implies \mathbf{v} =0 \end{align*}\]where $\mathbf{v}$ denotes the instantaneous object velocity. To convince yourself of the equivalence, consider that:

\[\mathrm{G}^T_n = \frac{\partial \mathbf{\psi}}{\partial \mathbf{q}}\]Due to the definition of the distance function and the grasp matrix and that $\mathbf{v} = \frac{\mathbf{q}}{dt}$. This means by simply dividing the original constraint by $dt$, we arrive at the equivalent velocity one. The implication in the constraint simply means that there is no set of object velocities that would lead to separation at any contact point. An equivalent formulation of this implication can be written for the set of contact forces applied to the object. Let’s denote the magnitude of the normal component of the contact force as $\mathbf{f}_{n}$, then a grasp has first order form closure iff:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G}_n \mathbf{f}_n & = - \mathbf{g} \quad \quad \forall \mathbf{g} \in \mathrm{R}^6 \\ \mathbf{f}_n & \geq 0 \end{align*}\]The physical interpretation of this condition is that equilibrium can be maintained under the assumption that contacts are frictionless. We emphasize that $\mathbf{f}_n$ is only the magnitude of the normal component of the contact force and no other components. Since $\mathbf{g}$ is any vector in $\mathrm{R}^6$, for the inequality to hold we require that $\mathbf{g}$ be in the range of $\mathrm{G}_n$. Consequently, the rank of $\mathrm{G}_n$ must be 6 for the vector to lie in its range for all values it can take.

We can also write the condition for first order form closure as there exists $\mathbf{f}_n$ such that the following two conditions hold:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G}_n \mathbf{f}_n & = 0 \\ \mathbf{f}_n & > 0 \end{align*}\]These conditions means that there exists a set of strictly compressive normal contact forces in the null space of $\mathrm{G}_n$. This also means that we can squeeze the object as tightly as we’d like while maintaining equilibrium (at no point will the object leave the grasp). If there were a combination of squeezing forces for which equilibrium did not hold, then the object would accelerate. Similarly, if we chose an external force along that direction, the object would leave the grasp. The search problem is now checking these conditions for all choices of $\mathbf{f}_n$. The first is a simple linear equality constraint, and the second is a linear strict inequality constraint. These checks are very easy to do with linear programs as we’ll see in the next subsection.

In general, for the above conditions to hold, Somov 1897 proved that at least 7 contacts are necessary for a 6 degree of freedom object and 4 are required for the planar case. Fig. 4 shows some example form closures in the plane (with 4 points of contact).

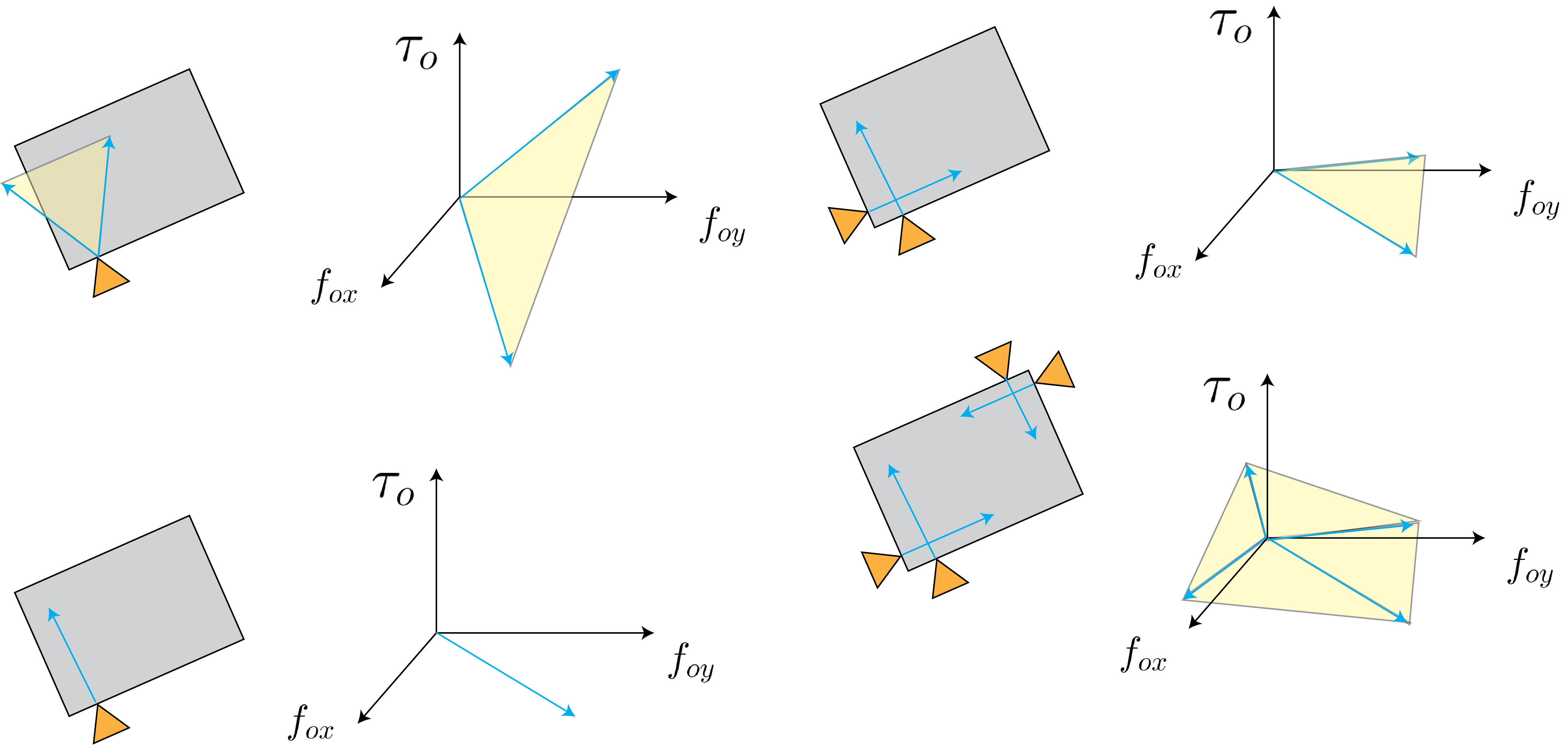

Geometrically, we can describe form closure using the composite friction cones we discussed in the previous sections. This idea is illustrated in Fig. 5. The top left panel shows the effect of having a frictional contact with a single finger. Notice the cone of forces the finger can apply. The bottom left panel is the same finger in the same location but with no friction. Notice that the set of forces it can apply is now just along a line and much more limited. Top right shows how the introduction of another finger (even though it is frictionless) significantly increases the set of wrenches we can apply to the object. The bottom right panel shows how with the introduction of two more well-placed fingers, we now have a wrench cone that spans the entire wrench space, resulting in a stable grasp. Note that the forces due to the fingers can only push, thus we need to have a positive span of the wrench space and that’s why we need 4 contacts. With 3 contacts, it is possible to have a span of the object wrench space, but this span would require negative contact forces which implies the contact pulls, which we are not allowing.

First order form closure tests

To test whether a grasp has form closure, we’d like to check whether we can find a $\mathbf{f}_n$ such that the following two conditions hold:

\[\begin{align} \mathrm{G}_n \mathbf{f}_n & = 0 \\ \mathbf{f}_n & > 0 \end{align}\]Let’s denote the smallest component of $\mathbf{f}_n$ as $d$. If we can find $d>0$, it would imply that $\mathbf{f}_n >0$. We can do this with the following linear program:

\[\begin{align} \textbf{LP1:} \quad \quad & \text{maximize} \quad \quad & d & \\ & \text{s.t.} & \mathrm{G}_n \mathbf{f}_n &= 0 \\ & & \mathrm{I} \mathbf{f}_n - \mathbf{1}d &\geq 0 \\ & & d & \geq 0 \\ & & \mathbf{1}^T \mathbf{f}_n &\leq N \\ \end{align}\]where $\mathrm{I}$ is the identity matrix and $\mathbf{1}$ is a vector with all components equal to 1. If this LP is infeasible or the optimal value $d^*$ is zero, then the grasp is not in form closure. We can formalize this procedure as follows:

Form Closure Test:

- Compute the rank of $\mathrm{G}_n$:

- If this rank is less than 4 in the planar case or 7 in the 3D case, then form closure does not exist;

- Else, the rank is adequate, proceed.

- Solve LP1:

- if $d^* = 0$ then form closure does not exist;

- if $d^* > 0$ then form closure exists and $d^*$ is a crude measure of how far the grasp is from losing form closure

Intuitively, if the smallest term in $\mathbf{f}_n$ is close to zero, then $\mathrm{G}_n$ is close to loosing rank which means that normal vectors of contacts are close to being dependent. This means that our grasp is close to losing form closure.

In summary, form closure is a fundamentally geometric constraint. It does not depend on frictional properties, rather it immobilizes the object using the concept of jamming. Form closure is a robust grasping strategy and a desirable one when it is possible to form. For the set of rigid-bodies, calculating form closure is equivalent to the solution of a linear program which can be done rapidly. One important drawback of form closure is the relatively large number of contacts required to produce it. In the following section, we study a different form of restraining that relies on contact mechanics and requires fewer contacts.

Force Closure

In form closure, we noted that the constraints against external wrenches and motion are entirely geometric. There was no need to consider forces but we did need a rather large number of contacts. In force closure, we require that the contacts can resist any object wrench (any set of external forces and torques applied to the center of mass of the object). The key difference is that we allow frictional forces to help maintain the grasp; i.e. resist the object wrench. The key contribution is then a reduced number of contacts by virtue of including frictional forces. In fact, for a 3D object, we only need 2 soft finger contacts or 3 hard finger contacts for force closure rather than the 7 needed in form closure.

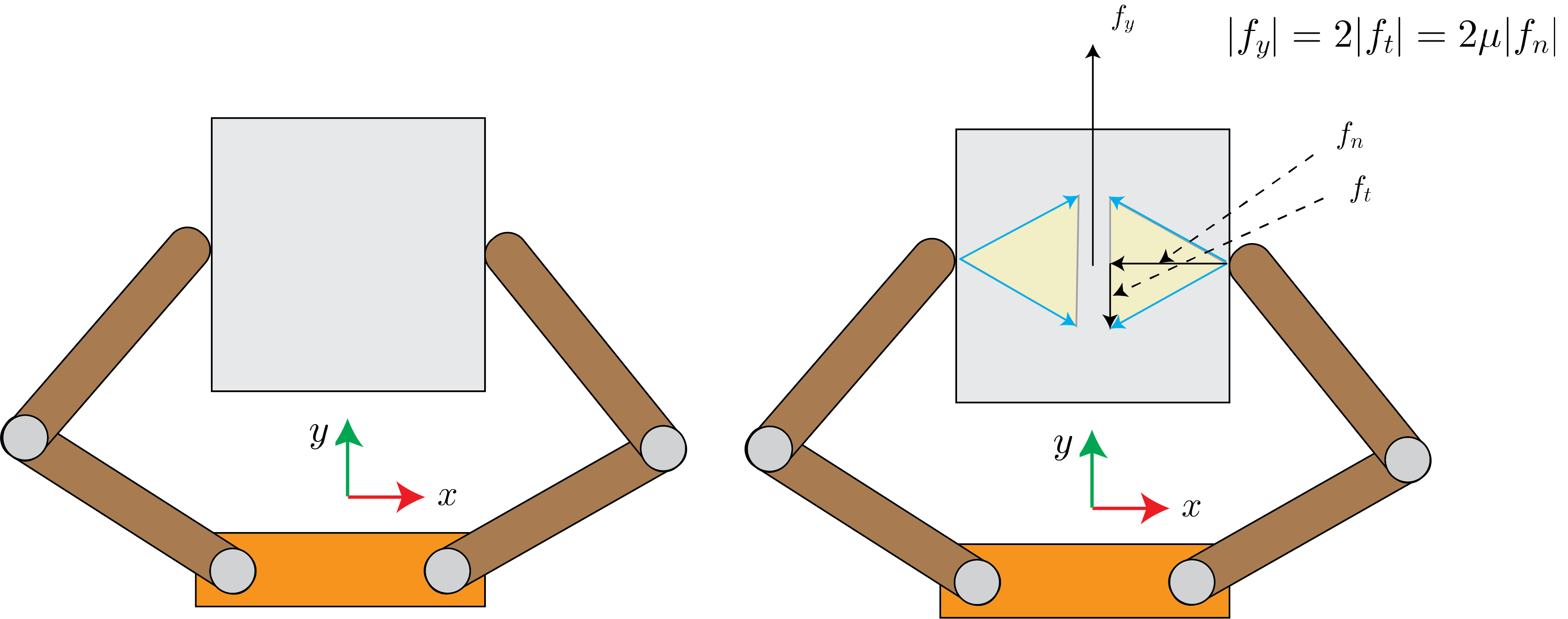

A fundamental requirement for form closure is that the hand/fingers must be able to squeeze arbitrarily tightly to account for any external wrench (no matter how large) applied to the object. For example, consider the object depicted in Fig.~\ref{fig:chap1:fc1}. The frictional force is able to resist any push we apply to the object along its $y$ axis with a line of action passing through the center of mass – as long as there is enough normal force to produce sufficient frictional tangent force.

Since our discussion depends heavily on the finger type (and contact type), let’s discuss 3 pervasive models:

Friction-free: This type of finger can only apply a force along the contact normal. It is not permitted to apply tangential/frictional forces. Imagine this type of finger as made of ice! We may write the contact force in the contact frame as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{f}_c = \begin{bmatrix} 0, & 0, & f_n, & 0, & 0, 0, & 0\end{bmatrix}^T \end{align*}\]Hard finger: The contact is well approximated by a point. It is allowed to transmit a normal force, and a tangential force in the contact plane.

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{f}_c = \begin{bmatrix} f_{t,1}, & f_{t,2}, & f_n, & 0, & 0, & 0\end{bmatrix}^T \end{align*}\]with the constraint that:

\[\begin{align*} \sqrt{f^2_{t,1} + f^2_{t,2}} \leq \mu f_n \end{align*}\]Soft finger: The contact is well approximated by a patch. The patch can transmit the same forces as a hard finger and an additional rotational torque, perpendicular to the contact plane.

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{f}_c = \begin{bmatrix} f_{t,1}, & f_{t,2}, & f_n, & 0, & 0, & \tau_p\end{bmatrix}^T \end{align*}\]with the constraint that:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{1}{\mu}\sqrt{f^2_{t,1} + f^2_{t,2}} + \frac{1}{\alpha \nu} \sqrt{\tau^2_p} \leq f_n \end{align*}\]where $\nu$ is the torsional friction coefficient and $\alpha$ is the characteristic length of the object to ensure consistency of units between the force and torque components.

We note that while these are 3 simple models, they do an excellent job of describing a large set of fingers that we may encounter. An important aspect of each of these definitions is that the contact reaction force lies in the friction cone induced by the type of contact and it’s specific parameters. Specifically, for the hard finger, we can write the Coulomb friction cone $\mathcal{F}$:

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{F} = \{ (f_n, f_{t,1}, f_{t,2}) \quad | \quad \sqrt{f^2_{t,1} + f^2_{t,2}} \leq \mu f_n \} \end{align*}\]and for the soft finger we can write the friction cone as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{F} = \{(f_n, f_{t,1}, f_{t,2}, \tau_p) \quad | \quad \frac{1}{\mu}\sqrt{f^2_{t,1} + f^2_{t,2}} + \frac{1}{\alpha \nu} \sqrt{\tau^2_p} \leq f_n \} \end{align*}\]Force Closure Definition

Recall from our form closure discussion that we defined a grasp as having form closure if:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G}_n \mathbf{f}_n & = - \mathbf{g} \\ \mathbf{f}_n &> 0 \end{align*}\]for all external wrenches applies to the object. In the definition of force closure, we still require that the grasp resists all external wrenches applied to the object. However, we have an additional constraint on the contact force: the contact force at the point of contact must be in the interior or on the boundary of the friction cone. We can express these conditions mathematically as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G} \mathbf{f}_c & = - \mathbf{g} \\ \mathbf{f}_c &\in \mathcal{F} \end{align*}\]where $\mathcal{F}$ denotes the composite friction cone as is defined as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathcal{F} = \mathcal{F}_1 \times ... \times \mathcal{F}_N = \{ \mathbf{f}_{c,i} \in \mathcal{F}_i; \quad i=1, ..., N \} \end{align*}\]The key differences between the two definitions (form and force closure) are:

- we use the full grasp matrix (since we have tangential forces as well as normal forces),

- we use the full contact wrench (rather than just the normal force applied by the contact force),

- the contact wrench must belong to the friction cone.

Due to \citet{murray1994mathematical}, a grasp is said to have \textbf{frictional force closure} iff the following two conditions hold:

\[\begin{align*} & rank(\mathrm{G}) = 3 \; (\text{planar}) \quad \text{or} \quad 6 \; (\text{3D}) \\ & \exists \mathbf{f}_c \; \text{s.t.} \; \; \mathrm{G}\mathbf{f}_c=0 \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{f}_c \in Interior(\mathcal{F}) \end{align*}\]A set of frictional contacts yields force closure if the positive span of the wrench cones is the entire wrench space. The rank condition means that the composite wrench cone spans the entire wrench space. For the second condition, since $\mathbf{f}_c \geq 0$ this ensures that the positive span of the wrench cones spans the entire wrench space.

Put another way, the first condition means that we want to span the space of all possible external wrenches exerted at the COM to be resisted by the contacts – if we cannot span this space, then there will be some subset of directions in which we cannot resist an external force. The second condition means there exists a set of reaction forces that span the null space of the grasp matrix and are in the interior of the composite friction cone. To understand better what this means, consider that we’d like to solve:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G}\mathbf{f}_c = -\mathbf{g} \end{align*}\]so we may write:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{f}_c = - \mathrm{G}^\dagger \mathbf{g} + \bar{\mathrm{G}} \mathbf{f}_{c,null} \end{align*}\]where the first term is the particular solution (pseudo inverse of $\mathrm{G}$ multiplied by the external wrench) and the second term $\bar{\mathrm{G}}$ (matrix with columns of the null space of $\mathrm{G}$) and $\mathbf{x}$ is the coefficient vector of the parameterization of the homogeneous solution. The set of internal contact forces:

\[\mathbf{f}_{c,int} = \bar{\mathrm{G}}\mathbf{f}_{c,null}\]do not affect the solution of the equation above; however, they play a key role in determining the stability of the grasp. They specify how tightly we can grasp the object. Without the null space, the grasp can at most resist only one particular value of externally applied wrenches.

The definition we provided above has one important short-coming. Can the fingers trying to attain force closure actually provide the necessary contact forces? We say that a grasp has force closure (a stronger condition than frictional force closure stated above) iff:

\[\begin{align*} & rank(\mathrm{G}) = 3 \; (\text{planar}) \quad \text{or} \quad 6 \; (\text{3D}) \\ & \mathcal{N}(\mathrm{G}) \cap \mathcal{N}(\mathrm{J}_f^T) = 0 \\ & \exists \mathbf{f}_c \; \text{s.t.} \; \; \mathrm{G}\mathbf{f}_c=0 \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{f}_c \in Interior(\mathcal{F}) \end{align*}\]where the second condition states that the null space of grasp matrix and the null space of finger Jacobians do not share any elements other than the zero vector. Intuitively, the grasp can inherently resist a set of contact forces described by the null space $\mathcal{N}(\mathrm{G})$. $\mathcal{N}(\mathrm{J}_f^T)$ specifies the set of contact forces the fingers can resist structurally but no joint torque can affect (make any changes to). If these two spaces share elements, then it means that there exists a set of contact forces that the grasp can inherently resist but that the fingers are incapable of producing. This implies the fingers are incapable of securely maintaining the grasp.

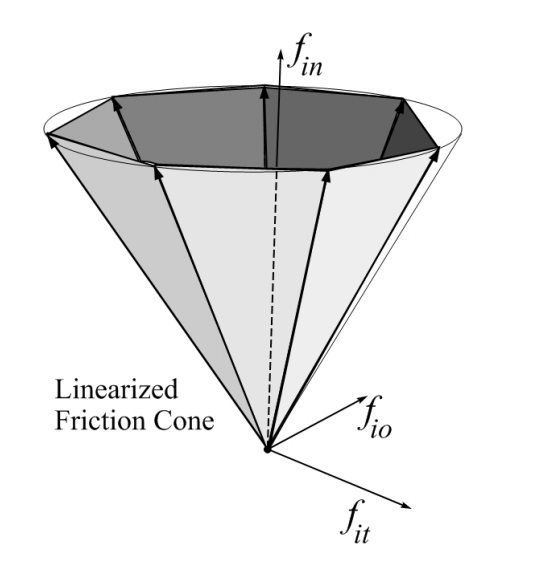

An important challenge in testing for force closure of a grasp is the quadratic/conic constraints imposed by the friction cones at the contacts. One approach to simplifying the test for force closure is to approximate the friction cone with polyhedral cone. Fig.~\ref{fig:chap1:lin-cone} shows an example of a linearized friction cone.

Any of the friction cones we have discussed so far (induced by the friction free, hard finger, or soft finger) can be approximated by the non-negative span of a finite number $n_g$ of generators $\mathbf{s}_{ij}$ of the friction cone. We can represent the set of applicable contact forces at contact $i$ as:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{G}_i \mathbf{f}_{c,i} = \mathrm{S}_i \mathbf{p}_i, \quad \mathrm{p}_i \geq 0 \end{align*}\]where:

\[\mathrm{S}_i = [\mathbf{s}_{i,1} \cdots \mathbf{s}_{i,n_g}]\]and $\mathbf{p}_i$ is a vector of non-negative generator weights. Let’s write the expressions for $\mathrm{S}_i$ for each type of contact:

Friction free: In this case the cone collapses to a line with $n_g = 1$ and:

\[\mathrm{S}_i = \begin{bmatrix}\hat{\mathbf{n}}_i^T \quad ((\mathbf{c}_i - \mathbf{p}) \times \hat{\mathbf{n}}_i)^T \end{bmatrix}^T\]Hard finger: The friction cone is represented by the non-negative sum of uniformly spaced contact force generators whose non-negative span approximates the Coulomb cone with an inscribed regular polyhedral cone. We can write:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{S}_i = \begin{bmatrix} \cdots & 1 & \cdots \\ \cdots & \mu_i \text{cos}(2k\pi/n_g) & \cdots \\ \cdots & \mu_i \text{sin}(2k\pi/n_g) & \cdots \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]where $k=1, \cdots, n_g$.

Soft finger: Since the torsional friction in this model is decoupled from the tangential friction, it’s generators are given by $[1 \; 0 \; 0 \; bv_i]^T$ and we can write:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{S}_i = \begin{bmatrix} \cdots & 1 & \cdots & 1 & 1 \\ \cdots & \mu_i \text{cos}(2k\pi/n_g) & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \cdots & \mu_i\text{sin}(2k\pi/n_g) & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \cdots & 0 & \cdots & bv_i & -bv_i \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]where $b$ is a characteristic length used to unify the units and $v_i$ is the torsional friction coefficient.

This polyhedral approximation to the friction cone allows us to efficiently represent the friction cone as a set of linear inequalities. To see this, we first note that adjacent generators span the faces of the polyhedral. Thus, by taking their cross-products, we get the surface normals to each face. By computing the dot product of the surface normals with the frictional force, we can check whether the force is in the interior or exterior of the cone. To formalize this idea, we can write:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{F}_i \mathbf{f}_{ci} \geq 0 \end{align*}\]where $\mathrm{F}_i$ is a matrix whose rows are composed of the normals to the faces formed by two adjacent generators of the approximate cone. E.g., for the hard finger contact:

\[i^{th} \quad \text{row of} \quad \mathrm{F}_i = \mathbf{s}_i \times \mathbf{s}_{i+1}\]where $\times$ is the cross-product.

The intuitive interpretation of the inequalities is that we require the reaction force to be in the interior of the space created by the intersection of the set of half planes making up the sides of the friction cone. We can compose the set of all contact and their reaction forces in the compact form:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{F} \mathbf{f}_{c} \geq 0 \end{align*}\]where:

\[\mathrm{F} = \text{BlockDiag}(\mathrm{F}_1, \cdots, \mathrm{F}_{n_c})\]We are now ready to test for force closure. Our procedure is as follows:

First: Compute the rank of $\mathrm{G}$:

- if the rank is 3 in the planar case or 6 in the 3D case, continue;

- else, force closure is not possible

Second: Solve the frictional form closure linear program (LP2):

\[\begin{align*} \textbf{LP2:} \quad \quad & \text{maximize} \quad \quad & d & \\ & \text{s.t.} & \mathrm{G} \mathbf{f}_c &= 0 \\ & & \mathrm{F} \mathbf{f}_c - \mathbf{1}d &\geq 0 \\ & & d & \geq 0 \\ & & \mathbf{e}^T \mathbf{f}_n &\leq N \end{align*}\]where the optimal value $d^*$ is a measure of the distance between the contact force and the boundary of the friction cone. The larger this value, the more stable the grasp.

If $d^*=0$ then force closure is not possible. Here we define:

\[\mathbf{e}_i = [1 \; 0\; 0\; 0\; 0\; 0]\]and:

\[\mathbf{e}=[\mathbf{e}_1, \cdots \mathbf{e}_{n_c}]\]where these vectors are responsible for picking out the normal component of the contact force for each contact.

Third: Solve the check for $\mathcal{N}(\mathrm{G}) \cap \mathcal{N}(\mathrm{J}^T)=0$ with LP3:

\[\begin{align*} \textbf{LP3:} \quad \quad & \text{maximize} \quad \quad & d & \\ & \text{s.t.} & \mathrm{G} \mathbf{f}_c &= 0 \\ & & \mathrm{J}^T\mathbf{f}_c & = 0 \\ & & \mathrm{E} \mathbf{f}_c - \mathbf{1}d &\geq 0 \\ & & d & \geq 0 \\ & & \mathbf{e}^T \mathbf{f}_n &\leq N \\ \end{align*}\]where:

\[\mathrm{E}=\text{BlockDiag}(\mathbf{e}_1, \cdots, \mathbf{e}_{n_c})\]If $d^*=0$ then force closure exists.

The polyhedral approximation to the friction cone is exact for the planar case and we can write:

\[\begin{align*} \mathrm{F}_i = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\mu^2_i}} \begin{bmatrix} \mu_i & 1 \\ \mu_i & -1 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]Antipodal Grasps and Parallel Jaw Grippers

Perhaps the most commonly used grippers in industry are simple two fingered parallel jaw grippers. Fig.~\ref{fig:yummy-push} shows one such example (the ABB Yumi end-effector). The popularity of this design is due to its simplicity in design (leading to highly reliable mechanisms that can perform hundreds of thousands of grasps if treated well) and control (a simple single degree of freedom linear stage).

Given the popularity of this type of gripper, here we’ll discuss a unique form of grasp analysis that is particularly well-suited for parallel jaw grippers: Antipodal grasps. A grasp is an ``antipodal” grasp iff the line connecting the contact points lies inside both friction cones. Antipodal grasps are a special type of force closure that are particularly amenable to parallel jaw grippers. We do note that it is impossible to get antipodal form closure for hard fingers unless there are more than two points of contact. In industrial applications, it is common to look for antipodal grasp affordances from visual feedback. We will investigate this approach more in our Perception for Manipulation section.